Atom

| Helium atom | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

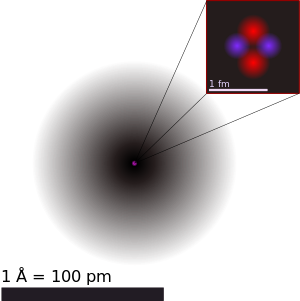

| An illustration of the helium atom, depicting the nucleus (pink) and the electron cloud distribution (black). The nucleus (upper right) in helium-4 is in reality spherically symmetric and closely resembles the electron cloud, although for more complicated nuclei this is not always the case. The black bar is one angstrom (10−10 m or 100 pm). | ||||||||

| Classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Properties | ||||||||

|

An atom is the smallest constituent unit of ordinary matter that has the properties of a chemical element.[1] Every solid, liquid,gas, and plasma is composed of neutral or ionized atoms. Atoms are very small; typical sizes are around 100 pm (a ten-billionth of a meter, in the short scale).[2] However, atoms do not have well-defined boundaries, and there are different ways to define their size that give different but close values.

Atoms are small enough that classical physics gives noticeably incorrect results. Through the development of physics, atomic models have incorporated quantum principles to better explain and predict the behavior.

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or moreprotons and typically a similar number of neutrons (none in hydrogen-1). Protons and neutrons are called nucleons. More than 99.94% of an atom's mass is in the nucleus. The protons have a positive electric charge, the electrons have a negative electric charge, and the neutrons have no electric charge. If the number of protons and electrons are equal, that atom is electrically neutral. If an atom has more or fewer electrons than protons, then it has an overall negative or positive charge, respectively, and it is called an ion.

The electrons of an atom are attracted to the protons in an atomic nucleus by this electromagnetic force. The protons and neutrons in the nucleus are attracted to each other by a different force, the nuclear force, which is usually stronger than the electromagnetic force repelling the positively charged protons from one another. Under certain circumstances the repelling electromagnetic force becomes stronger than the nuclear force, and nucleons can be ejected from the nucleus, leaving behind a different element: nuclear decay resulting in nuclear transmutation.

The number of protons in the nucleus defines to what chemical element the atom belongs: for example, all copper atoms contain 29 protons. The number of neutrons defines the isotope of the element.[3] The number of electrons influences themagnetic properties of an atom. Atoms can attach to one or more other atoms by chemical bonds to form chemical compounds such as molecules. The ability of atoms to associate and dissociate is responsible for most of the physical changes observed in nature, and is the subject of the discipline of chemistry.

Structure

Subatomic particles

Though the word atom originally denoted a particle that cannot be cut into smaller particles, in modern scientific usage the atom is composed of various subatomic particles. The constituent particles of an atom are the electron, the proton and the neutron; all three are fermions. However, the hydrogen-1 atom has no neutrons and the hydron ion has no electrons.

The electron is by far the least massive of these particles at 9.11×10−31 kg, with a negative electrical charge and a size that is too small to be measured using available techniques.[33] It is the lightest particle with a positive rest mass measured. Under ordinary conditions, electrons are bound to the positively charged nucleus by the attraction created from opposite electric charges. If an atom has more or fewer electrons than its atomic number, then it becomes respectively negatively or positively charged as a whole; a charged atom is called an ion. Electrons have been known since the late 19th century, mostly thanks to J.J. Thomson; see history of subatomic physics for details.

Protons have a positive charge and a mass 1,836 times that of the electron, at 1.6726×10−27 kg. The number of protons in an atom is called its atomic number. Ernest Rutherford (1919) observed that nitrogen under alpha-particle bombardment ejects what appeared to be hydrogen nuclei. By 1920 he had accepted that the hydrogen nucleus is a distinct particle within the atom and named it proton.

Neutrons have no electrical charge and have a free mass of 1,839 times the mass of the electron,[34] or 1.6929×10−27 kg, the heaviest of the three constituent particles, but it can be reduced by the nuclear binding energy. Neutrons and protons (collectively known as nucleons) have comparable dimensions—on the order of 2.5×10−15 m—although the 'surface' of these particles is not sharply defined.[35] The neutron was discovered in 1932 by the English physicist James Chadwick.

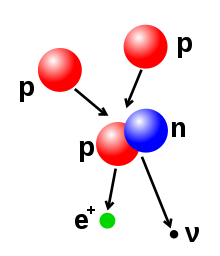

In the Standard Model of physics, electrons are truly elementary particles with no internal structure. However, both protons and neutrons are composite particles composed ofelementary particles called quarks. There are two types of quarks in atoms, each having a fractional electric charge. Protons are composed of two up quarks (each with charge +23) and one down quark (with a charge of −13). Neutrons consist of one up quark and two down quarks. This distinction accounts for the difference in mass and charge between the two particles.[36][37]

The quarks are held together by the strong interaction (or strong force), which is mediated by gluons. The protons and neutrons, in turn, are held to each other in the nucleus by the nuclear force, which is a residuum of the strong force that has somewhat different range-properties (see the article on the nuclear force for more). The gluon is a member of the family of gauge bosons, which are elementary particles that mediate physical forces.[36][37]

Nucleus

All the bound protons and neutrons in an atom make up a tiny atomic nucleus, and are collectively called nucleons. The radius of a nucleus is approximately equal to 1.07 3√A fm, where A is the total number of nucleons.[38] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[39]

Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons, called the atomic number. Within a single element, the number of neutrons may vary, determining the isotope of that element. The total number of protons and neutrons determine the nuclide. The number of neutrons relative to the protons determines the stability of the nucleus, with certain isotopes undergoing radioactive decay.[40]

The proton, the electron, and the neutron are classified as fermions. Fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principlewhich prohibits identical fermions, such as multiple protons, from occupying the same quantum state at the same time. Thus, every proton in the nucleus must occupy a quantum state different from all other protons, and the same applies to all neutrons of the nucleus and to all electrons of the electron cloud. However, a proton and a neutron are allowed to occupy the same quantum state.[41]

For atoms with low atomic numbers, a nucleus that has more neutrons than protons tends to drop to a lower energy state through radioactive decay so that the neutron–proton ratio is closer to one. However, as the atomic number increases, a higher proportion of neutrons is required to offset the mutual repulsion of the protons. Thus, there are no stable nuclei with equal proton and neutron numbers above atomic number Z = 20 (calcium) and as Z increases, the neutron–proton ratio of stable isotopes increases.[41] The stable isotope with the highest proton–neutron ratio is lead-208 (about 1.5).

The number of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus can be modified, although this can require very high energies because of the strong force. Nuclear fusion occurs when multiple atomic particles join to form a heavier nucleus, such as through the energetic collision of two nuclei. For example, at the core of the Sun protons require energies of 3–10 keV to overcome their mutual repulsion—the coulomb barrier—and fuse together into a single nucleus.[42] Nuclear fission is the opposite process, causing a nucleus to split into two smaller nuclei—usually through radioactive decay. The nucleus can also be modified through bombardment by high energy subatomic particles or photons. If this modifies the number of protons in a nucleus, the atom changes to a different chemical element.[43][44]

If the mass of the nucleus following a fusion reaction is less than the sum of the masses of the separate particles, then the difference between these two values can be emitted as a type of usable energy (such as a gamma ray, or the kinetic energy of a beta particle), as described by Albert Einstein's mass–energy equivalence formula, E = mc2, where m is the mass loss and c is the speed of light. This deficit is part of the binding energy of the new nucleus, and it is the non-recoverable loss of the energy that causes the fused particles to remain together in a state that requires this energy to separate.[45]

The fusion of two nuclei that create larger nuclei with lower atomic numbers than iron and nickel—a total nucleon number of about 60—is usually an exothermic process that releases more energy than is required to bring them together.[46] It is this energy-releasing process that makes nuclear fusion in stars a self-sustaining reaction. For heavier nuclei, the binding energy per nucleon in the nucleus begins to decrease. That means fusion processes producing nuclei that have atomic numbers higher than about 26, and atomic masses higher than about 60, is an endothermic process. These more massive nuclei can not undergo an energy-producing fusion reaction that can sustain the hydrostatic equilibrium of a star.[41]

Electron cloud

The electrons in an atom are attracted to the protons in the nucleus by the electromagnetic force. This force binds the electrons inside anelectrostatic potential well surrounding the smaller nucleus, which means that an external source of energy is needed for the electron to escape. The closer an electron is to the nucleus, the greater the attractive force. Hence electrons bound near the center of the potential well require more energy to escape than those at greater separations.

Electrons, like other particles, have properties of both a particle and a wave. The electron cloud is a region inside the potential well where each electron forms a type of three-dimensional standing wave—a wave form that does not move relative to the nucleus. This behavior is defined by an atomic orbital, a mathematical function that characterises the probability that an electron appears to be at a particular location when its position is measured.[47] Only a discrete (or quantized) set of these orbitals exist around the nucleus, as other possible wave patterns rapidly decay into a more stable form.[48] Orbitals can have one or more ring or node structures, and differ from each other in size, shape and orientation.[49]

Each atomic orbital corresponds to a particular energy level of the electron. The electron can change its state to a higher energy level by absorbing a photon with sufficient energy to boost it into the new quantum state. Likewise, through spontaneous emission, an electron in a higher energy state can drop to a lower energy state while radiating the excess energy as a photon. These characteristic energy values, defined by the differences in the energies of the quantum states, are responsible for atomic spectral lines.[48]

The amount of energy needed to remove or add an electron—the electron binding energy—is far less than the binding energy of nucleons. For example, it requires only 13.6 eV to strip a ground-state electron from a hydrogen atom,[50] compared to 2.23 million eV for splitting a deuterium nucleus.[51] Atoms are electrically neutral if they have an equal number of protons and electrons. Atoms that have either a deficit or a surplus of electrons are called ions. Electrons that are farthest from the nucleus may be transferred to other nearby atoms or shared between atoms. By this mechanism, atoms are able to bond into molecules and other types of chemical compounds likeionic and covalent network crystals.

History of atomic theory

Atoms in philosophy

The idea that matter is made up of discrete units is a very old idea, appearing in many ancient cultures such as Greece and India. The word "atom" was coined by ancient Greek philosophers. However, these ideas were founded in philosophical and theological reasoning rather than evidence and experimentation. As a result, their views on what atoms look like and how they behave were incorrect. They also could not convince everybody, so atomism was but one of a number of competing theories on the nature of matter. It was not until the 19th century that the idea was embraced and refined by scientists, when the blossoming science of chemistry produced discoveries that only the concept of atoms could explain.

First evidence-based theory

In the early 1800s, John Dalton used the concept of atoms to explain why elements always react in ratios of small whole numbers (the law of multiple proportions). For instance, there are two types of tin oxide: one is 88.1% tin and 11.9% oxygen and the other is 78.7% tin and 21.3% oxygen (tin(II) oxide and tin dioxide respectively). This means that 100g of tin will combine either with 13.5g or 27g of oxygen. 13.5 and 27 form a ratio of 1:2, a ratio of small whole numbers. This common pattern in chemistry suggested to Dalton that elements react in whole number multiples of discrete units—in other words, atoms. In the case of tin oxides, one tin atom will combine with either one or two oxygen atoms.[4]

Dalton also believed atomic theory could explain why water absorbs different gases in different proportions. For example, he found that water absorbs carbon dioxide far better than it absorbs nitrogen.[5] Dalton hypothesized this was due to the differences in mass and complexity of the gases' respective particles. Indeed, carbon dioxide molecules (CO2) are heavier and larger than nitrogen molecules (N2).

Brownian motion

In 1827, botanist Robert Brown used a microscope to look at dust grains floating in water and discovered that they moved about erratically, a phenomenon that became known as "Brownian motion". This was thought to be caused by water molecules knocking the grains about. In 1905 Albert Einsteinproved the reality of these molecules and their motions by producing the first Statistical physics analysis of Brownian motion.[6][7][8] French physicist Jean Perrin used Einstein's work to experimentally determine the mass and dimensions of atoms, thereby conclusively verifying Dalton's atomic theory.[9]

Discovery of the electron

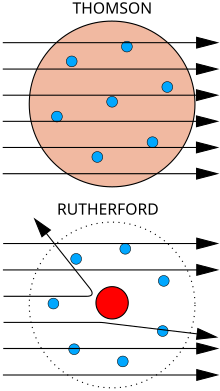

The physicist J. J. Thomson measured the mass of cathode rays, showing they were made of particles, but were around 1800 times lighter than the lightest atom, hydrogen. Therefore, they were not atoms, but a new particle, the first subatomic particle to be discovered, which he originally called "corpuscle" but was later named electron, after particles postulated by George Johnstone Stoney in 1874. He also showed they were identical to particles given off by photoelectric and radioactive materials.[10] It was quickly recognized that they are the particles that carry electric currents in metal wires, and carry the negative electric charge within atoms. Thomson was given the 1906Nobel Prize in Physics for this work. Thus he overturned the belief that atoms are the indivisible, ultimate particles of matter.[11] Thomson also incorrectly postulated that the low mass, negatively charged electrons were distributed throughout the atom in a uniform sea of positive charge. This became known as the plum pudding model.

Discovery of the nucleus

In 1909, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under the direction of Ernest Rutherford, bombarded a metal foil with alpha particles to observe how they scattered. They expected all the alpha particles to pass straight through with little deflection, because Thomson's model said that the charges in the atom are so diffuse that their electric fields could not affect the alpha particles much. However, Geiger and Marsden spotted alpha particles being deflected by angles greater than 90°, which was supposed to be impossible according to Thomson's model. To explain this, Rutherford proposed that the positive charge of the atom is concentrated in a tiny nucleus at the center of the atom.[12]

Discovery of isotopes

While experimenting with the products of radioactive decay, in 1913 radiochemist Frederick Soddy discovered that there appeared to be more than one type of atom at each position on the periodic table.[13] The term isotope was coined by Margaret Todd as a suitable name for different atoms that belong to the same element. J.J. Thomson created a technique for separating atom types through his work on ionized gases, which subsequently led to the discovery of stable isotopes.[14]

Bohr model

In 1913 the physicist Niels Bohr proposed a model in which the electrons of an atom were assumed to orbit the nucleus but could only do so in a finite set of orbits, and could jump between these orbits only in discrete changes of energy corresponding to absorption or radiation of a photon.[15] This quantization was used to explain why the electrons orbits are stable (given that normally, charges in acceleration, including circular motion, lose kinetic energy which is emitted as electromagnetic radiation, see synchrotron radiation) and why elements absorb and emit electromagnetic radiation in discrete spectra.[16]

Later in the same year Henry Moseley provided additional experimental evidence in favor of Niels Bohr's theory. These results refinedErnest Rutherford's and Antonius Van den Broek's model, which proposed that the atom contains in its nucleus a number of positivenuclear charges that is equal to its (atomic) number in the periodic table. Until these experiments, atomic number was not known to be a physical and experimental quantity. That it is equal to the atomic nuclear charge remains the accepted atomic model today.

Chemical bonding explained

Chemical bonds between atoms were now explained, by Gilbert Newton Lewis in 1916, as the interactions between their constituent electrons.[18] As the chemical properties of the elements were known to largely repeat themselves according to the periodic law,[19] in 1919 the American chemist Irving Langmuirsuggested that this could be explained if the electrons in an atom were connected or clustered in some manner. Groups of electrons were thought to occupy a set of electron shells about the nucleus.[20]

Further developments in quantum physics

The Stern–Gerlach experiment of 1922 provided further evidence of the quantum nature of the atom. When a beam of silver atoms was passed through a specially shaped magnetic field, the beam was split based on the direction of an atom's angular momentum, or spin. As this direction is random, the beam could be expected to spread into a line. Instead, the beam was split into two parts, depending on whether the atomic spin was oriented up or down.[21]

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed that all particles behave to an extent like waves. In 1926, Erwin Schrödinger used this idea to develop a mathematical model of the atom that described the electrons as three-dimensional waveforms rather than point particles. A consequence of using waveforms to describe particles is that it is mathematically impossible to obtain precise values for both the position and momentum of a particle at a given point in time; this became known as the uncertainty principle, formulated byWerner Heisenberg in 1926. In this concept, for a given accuracy in measuring a position one could only obtain a range of probable values for momentum, and vice versa.[22]This model was able to explain observations of atomic behavior that previous models could not, such as certain structural and spectral patterns of atoms larger than hydrogen. Thus, the planetary model of the atom was discarded in favor of one that described atomic orbital zones around the nucleus where a given electron is most likely to be observed.[23][24]

Discovery of the neutron

The development of the mass spectrometer allowed the mass of atoms to be measured with increased accuracy. The device uses a magnet to bend the trajectory of a beam of ions, and the amount of deflection is determined by the ratio of an atom's mass to its charge. The chemist Francis William Aston used this instrument to show that isotopes had different masses. The atomic mass of these isotopes varied by integer amounts, called the whole number rule.[25] The explanation for these different isotopes awaited the discovery of the neutron, an uncharged particle with a mass similar to the proton, by the physicist James Chadwick in 1932. Isotopes were then explained as elements with the same number of protons, but different numbers of neutrons within the nucleus.[26]

Fission, high-energy physics and condensed matter

In 1938, the German chemist Otto Hahn, a student of Rutherford, directed neutrons onto uranium atoms expecting to get transuranium elements. Instead, his chemical experiments showed barium as a product.[27] A year later, Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch verified that Hahn's result were the first experimental nuclear fission.[28][29] In 1944, Hahn received the Nobel prize in chemistry. Despite Hahn's efforts, the contributions of Meitner and Frisch were not recognized.[30]

In the 1950s, the development of improved particle accelerators and particle detectors allowed scientists to study the impacts of atoms moving at high energies.[31] Neutrons and protons were found to be hadrons, or composites of smaller particles called quarks. The standard model of particle physics was developed that so far has successfully explained the properties of the nucleus in terms of these sub-atomic particles and the forces that govern their interactions.

No comments:

Post a Comment